Genetic Testing

Discover the benefits of getting tested for genes that can cause Dravet Syndrome and what is involved.

Between 85-90% of people with a diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome have a change (mutation or deletion) in the gene known as SCN1A. This is short for ‘sodium channel alpha 1 subunit’.

The SCN1A gene contains instructions, or genetic code, to create an important protein in the brain, known as a ‘sodium ion channel’. The movement of sodium ions in and out of nerve cells helps to control electrical messages in the brain. A change, or mutation, in the code of the SCN1A gene can lead to the faulty functioning of this protein.

Each person has two copies of the SCN1A gene – one from each parent. Many of the gene mutations found in Dravet Syndrome prevent one of these two copies from working as it should. That leaves only one functional copy of the SCN1A gene.

If one of the SCN1A copies is not working properly, not enough sodium ion channel protein is made. The faulty protein can cause the person with the SCN1A mutation to experience seizures and a variety of other conditions.

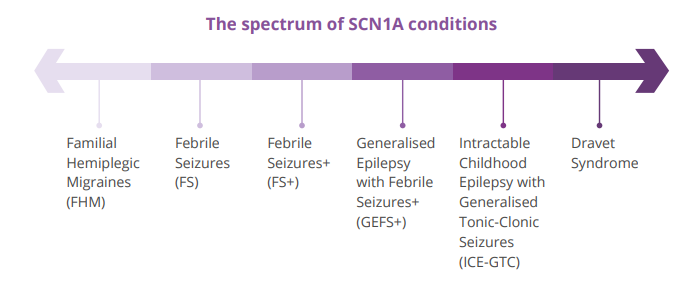

But having a mutation in the SCN1A gene doesn’t necessarily lead to Dravet Syndrome. There is a spectrum of SCN1A conditions. Dravet Syndrome lies at the severe end of that spectrum. Other SCN1A mutations are associated with less severe forms of epilepsy, such as Genetic Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures+ (GEFS+).

SCN1A mutations can occur in many different parts of the gene so someone with Dravet Syndrome is unlikely to have exactly the same mutation as another person with the condition.

For a small amount of people, a clinical diagnosis of Dravet Syndrome is linked to a change in genes other than SCN1A.

In most cases, people who have a gene change that isn’t SCN1A have a different neurological condition. They will have different seizures and characteristics and comorbidities to those with SCN1A-related Dravet Syndrome and may respond differently to medications. But some people with these genetic variations can have very similar symptoms to Dravet Syndrome.

Around 10 to 15% of people with Dravet Syndrome either have no detected SCN1A change, or have mutation(s) in genes other than SCN1A. It may be that the SCN1A mutation does exist in these people, but scientists can’t identify it yet. Or there could be other factors other than the gene mutation at play.

Other genes that might have a role in causing Dravet Syndrome include:

Mutations of this gene have been found in people with a variety of syndromes including:

Unlike people with SCN1A-related Dravet Syndrome, those with a SCN2A mutation may respond positively to sodium channel blockers as a treatment for seizures.

Unlike those with Dravet Syndrome, people who have this gene mutation:

This mutation has been found in several people with GEFS+ Dravet Syndrome. People who have a SCN1B mutation and Dravet Syndrome share very similar characteristics to those with the condition who have a change in the SCN1A gene. This includes developing Dravet Syndrome in early childhood, treatment-resistant seizures, intellectual disability and other comorbidities.

Although PCDH19 epilepsy is considered to be a distinct syndrome, it mimics Dravet Syndrome in several ways. Differences are:

As well as people with Dravet Syndrome, mutations of this gene have been found in several epilepsies, including:

Changes in GABRG2 have been found in a small number of people with GEFS+ or Dravet Syndrome.

Changes in this gene have been found in people with Ohtahara syndrome, West syndrome, and non-specific epilepsies. They have varying levels of intellectual disability and movement disorders.

In some people, a change in this gene very closely resembles classic Dravet Syndrome.

People with Dravet Syndrome who have CHD2 mutations experience their first seizures later than normal – between one to three years old. People with Jeavons syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and other epilepsies, can have a change in this gene.

People who have Dravet Syndrome with this change have become seizure-free as adults. This doesn’t normally happen when someone has Dravet Syndrome.

No, it shouldn’t. Dravet Syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. Everyone who has the condition should have access to appropriate therapies and support, regardless of what gene caused Dravet Syndrome to happen.

Here at Dravet Syndrome UK, we support all families living with Dravet Syndrome. Several members of our community have genetic mutations other than SCN1A.

Our Family Support Manager, Teresa, has an adult daughter whose genetic test revealed a SCN1B mutation. You can read Teresa’s and Amy’s story here.

Many thanks to our Medical Advisory Board member, Andreas Brunklaus, for his assistance in writing this content.

Discover the benefits of getting tested for genes that can cause Dravet Syndrome and what is involved.

Read about gene-based therapies that are currently being explored for Dravet Syndrome and what this might mean for future treatment.

Discover more about the background of this relatively newly diagnosed condition.

Find out how Dravet Syndrome develops when one of the genes in a part of the brain doesn’t function as it should.